To fix a source of waste contamination in freshwater or water infrastructure networks, we need to find where the source is. This begins with understand what’s happening at the microscopic level and following the microbes back to where they started.

Despite the thought being uncomfortable for some, most of us are aware that we have microorganisms living inside us. The makeup of these microbes in our system will change and adapt depending on what we are exposed to, and while many of these microbes are good for us, or even required by our bodies, there are others that can be very harmful.

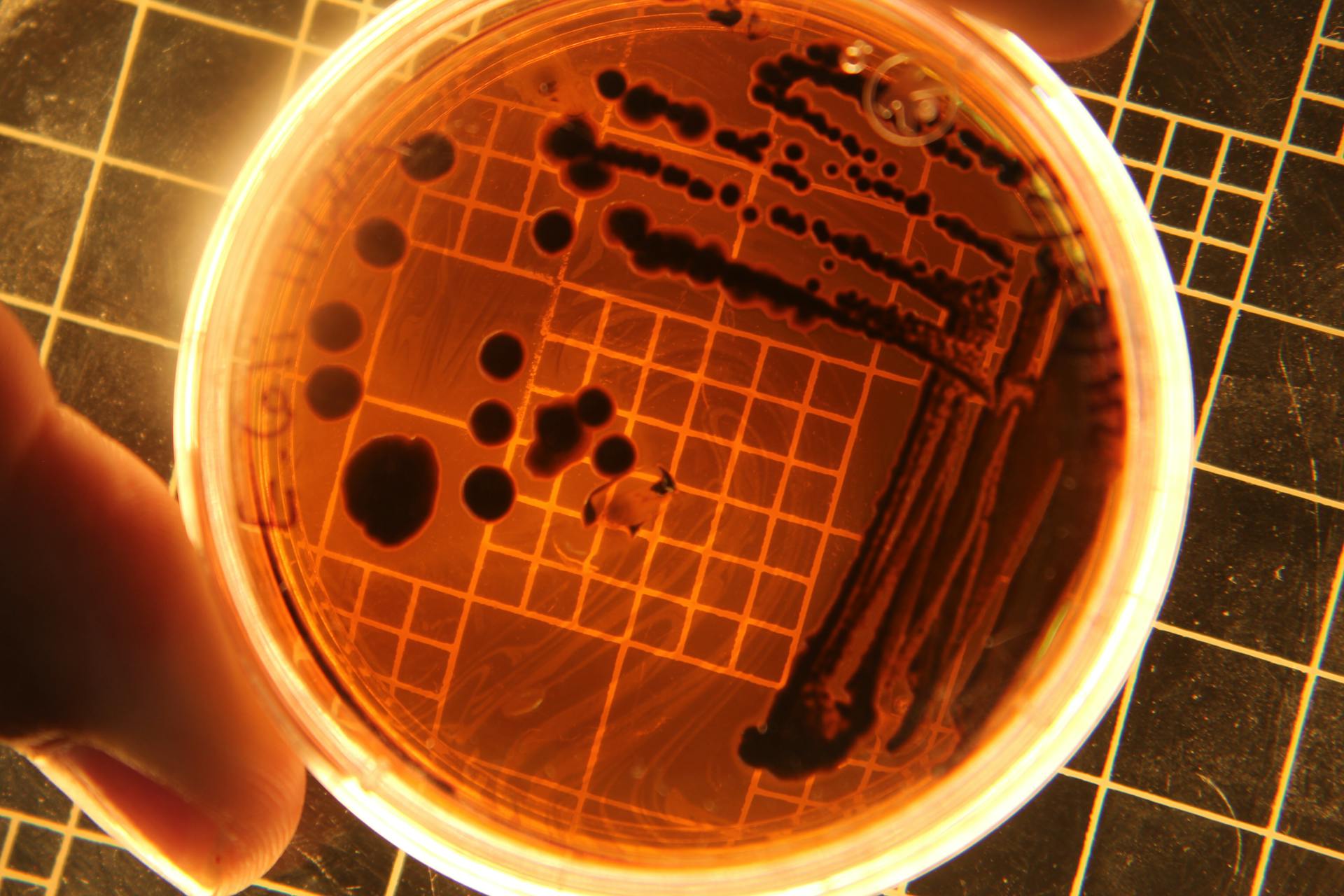

Escherichia coli (E. coli) are bacteria that live in the digestive system of warm-blooded animals, including humans. There are many strains of E. coli and most of the time, E. coli plays a beneficial role in our gut biome. However, there some strains of E. coli that can cause disease – pathogenic E.coli, particularly if ingested.

E. coli is prevalent in the digestive system of warm-blooded mammals and in faecal matter. Therefore, E. coli makes a good indicator that water is contaminated with faecal matter, not just from humans, but from many warm-blooded animals including most livestock. In these cases, E. coli can cause disease on its own, but more importantly it is easy to test for and near-definitive proof of contamination of faecal matter. Rather than testing for every possible pathogen associated with faecal matter, E. coli becomes a clear indicator that there may be other, more harmful pathogens in the water being tested, such as Campylobacter.

The ease of testing for E. coli means regular monitoring is typically ongoing in many water networks, freshwater systems and even some coastal marine environments. We have guidelines for expected and overly high levels of E. coli values outlined in the National Policy for Freshwater Management (NPS:FM) that are used in regular monitoring to know when to raise the alarm of high contamination levels.

When we do detect high levels of contamination, it is generally due to exposure from human settlements, agricultural areas and even wild animal gatherings, such as duck ponds. The next step becomes finding the origin to be able to remove the contamination from its source.

Potential sources can come from a multitude of issues including broken sewage pipes, wastewater overflows, agricultural runoff, or even failing water treatment devices to name a few. With this wide range of potentials, we begin by eliminating options using our microbial source tracking methodology.

E. coli is species of bacteria, with different strains based on small genetic changes that encode how the bacteria operate. Bacteria require less genetic material to encode instructions for life, and contain less redundancy within their genetic code, which means that small genetic changes in bacteria often result in larger functional changes than what would be observed with same genetic change in multi-cellular organisms.

These strains differ depending on the host species they inhabit, and utilising DNA analysis of the detected E. coli, we can determine if the bacteria came from a human, bovine, canine, waterfowl or more. This helps us narrow down the source type, whether it is most likely agricultural, wildlife or infrastructure in origin.

Depending on where the test occurred, further strategic testing locations can help determine the source from there. As an example, if there is a fork where two streams merge into one, we can test upstream of the merge to understand if the contamination is in one stream, but not the other, helping us narrow down the original source.

Piecing this information together, we can identify where the contamination has occurred.

When we have established the contamination source, we present our findings and, where appropriate for the project, recommend actions to resolve the issue. Remediation could include redesigning or renewing failing infrastructure, but there are also cases where pathogen count can be used as evidence in pursuing legal action against polluting sources.

Microbial source tracking forms a part of the contingency plans for most modern water monitoring programmes around the motu.

Regular monitoring programmes are included in catchment management plans that are developed for councils and their communities. These plans follow the goals of enabling Te Mana o Te Wai to improve the health of water, ecosystems and people. Together, this ongoing monitoring with microbial source tracking becomes a powerful tool to enable care for our communities and our environment.

.jpg)

.jpg)